Bigger. Greener. Teeming with exotic life. This is what Australia looked like 75,000 years ago.

And when the first hunter-gatherers crossed the narrow strait from East Timor – then at the tip of a much larger Southeast Asian landmass – they found a land unlike any other they had previously experienced.

It was inhabited by giant beasts. And it offered some 2 million square kilometres of hospitable coastal plains than it has now.

But it was already – slowly but steadily – changing.

An interdisciplinary team from the University of Sydney, Southern Cross University, Flinders University and Université Grenoble-Alpes has been tracking this change.

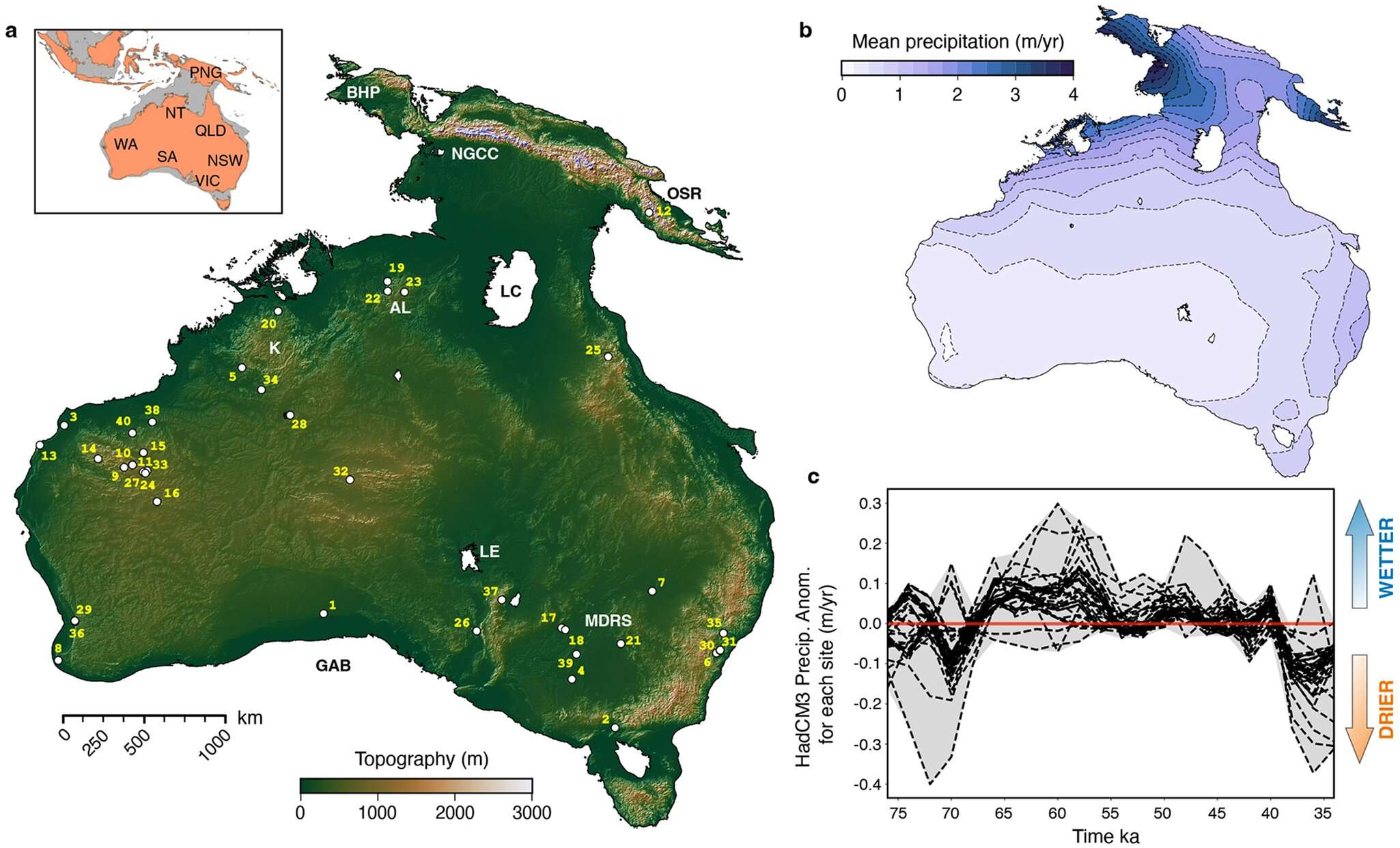

Their computerised landscape evolution model identifies shifts in climate, the impact this had on regional ecologies – and how that may have shaped human migration patterns across tens of thousands of years.

At first, much of the world’s oceans were locked up in the north and south poles. Landlocked glaciers were far larger than they are today.

That meant sea levels were not high enough to spill across the continental shelf linking mainland Australia to Tasmania and Papua New Guinea. This single connected continent has been dubbed “Sahul”.

A Sahul topography of around 65,000 years ago assuming a coastline at 85m lower sea levels than present. Credit: Nature Communications

But, starting about 25,000 years ago, the sea began its steady – but relentless – march forward.

Many First Nations campsites were gradually inundated as seas edged between 80m and 120m upwards to where they are today. Some of these have since been discovered and documented by archaeologists.

But who settled where, when – and why – remains something of a puzzle.The magical land of OzThe study identifies two potential crossing points from Asia into Sahul available to ancient seafarers.One route was through West Papua (about 73,000 years ago) and down through northern Queensland and what is now the Gulf (then a lake) of Carpentaria.Another was across the Timor Sea shelf (about 75,000 years ago) and into the Kimberley.

Giant iguanas. Giant kangaroos. Giant koalas.These were scattered across the landscape. But scientists believe their numbers had already long been in decline because of increasing aridity. And the arrival of a new predator – humans – may have sped up their demise.

Last month, the Museums Victoria Research Institute revealed the remarkably well-preserved skeleton of a 50,000-year-old “short-faced” kangaroo.

Long extinct, it didn’t hop. It walked with what researchers describe as a “striding gait … similar to that of humans or Tyrannosaurus rex”.

Palaeontologist Tim Ziegler with the fossil skeleton at Museums Victoria Research Institute. Photo by Tim Carrafa. Credit: Museums Victoria

Following, and fleeing, water

“One aspect that has been mostly overlooked when evaluating this spread of first humans across Sahul is the impact of climate-driven evolution of Earth surface geography which took place during the time of migration,” says co-author Associate Professor Ian Moffat of Flinders University.

As Australia’s climate gradually shifted over the millennia, its Aboriginal settlers were forced to adapt. Sea levels rose. Temperatures warmed. The land began to dry out.

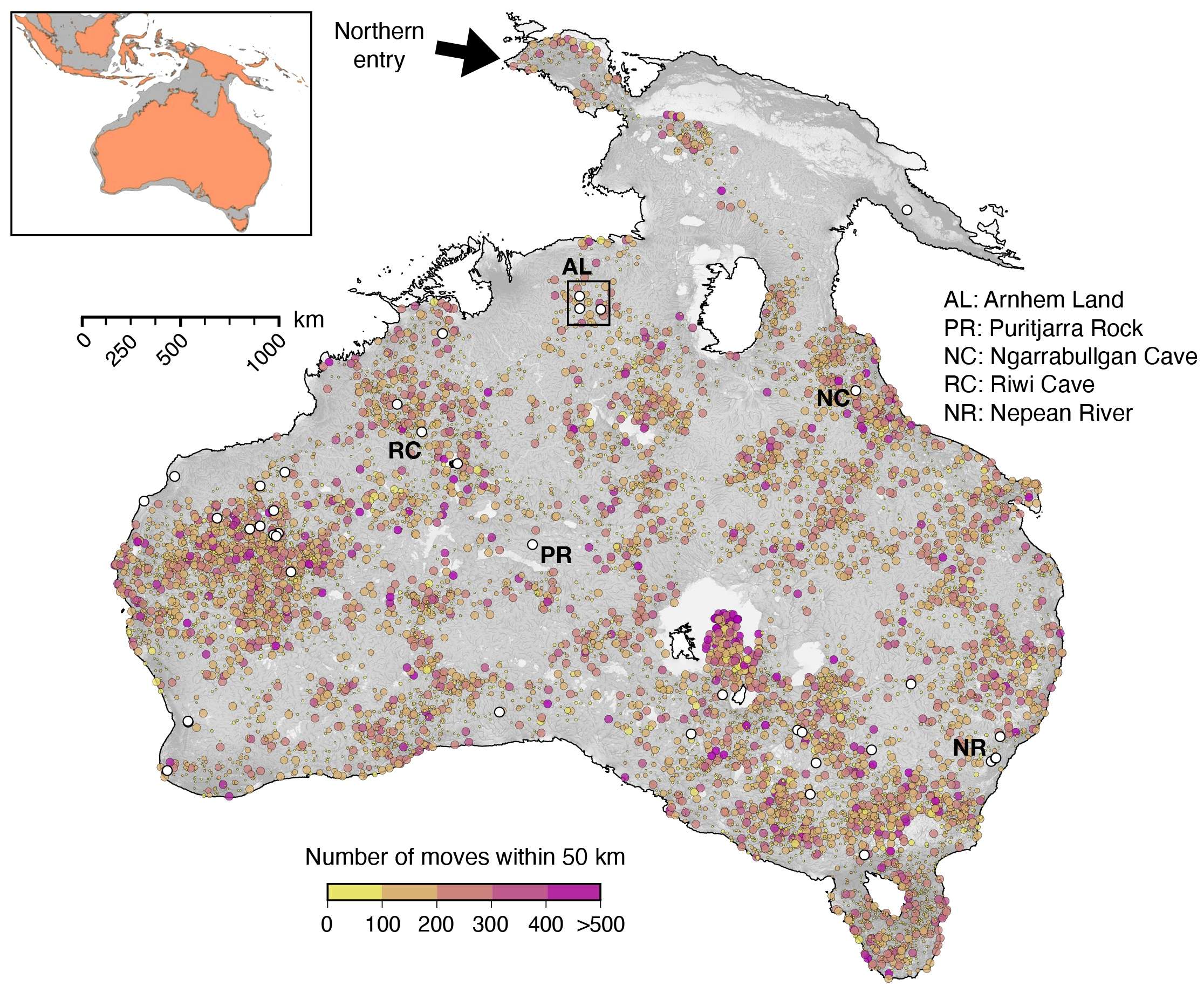

The new study ran thousands of simulations to determine where the landscape was most suitable for human habitation at different points over the following 40,000 years. And that’s being used to narrow down potential migration routes nationwide.

When combined with dates obtained from known archaeological sites, the simulations suggest that First Nations peoples gradually expanded their settlements at roughly 0.36km and 1.15km per year.

“Based on our model, we didn’t identify well-defined migration routes. Instead, we saw a “radiating wave” of migrations,” the study’s authors write.

“We found that human settlers would have dispersed across the continental interior along rivers on both sides of Lake Carpentaria (the modern Gulf of Carpentaria).”

The first communities would have mainly been foraging along the way, following water streams. They also travelled along the receding coastlines as sea levels rose once more.”

Predicted migration routes passing through 34 of the 40 known archaeological sites from that period. Credit: Nature Communications

The dawn of fire

A separate study by James Cook University indicates fire management techniques were invented at least 11,000 years ago. And this further shaped Australia’s environment – shifting the pattern away from one of seasonal high-intensity fires started by lightning to less damaging patchwork burning.

Professor Michael Bird and his team took an 18-metre-deep sediment core from Girraween Lagoon on the outskirts of Darwin for the study. Shifts in pollen, sediment and charcoal concentrations track this change.

“The Girraween record is one of the few long-term climate records that covers the period before people arrived in Australia 65,000 years ago, as well as after,” Prof Bird said.

Much of this traditional fire management ceased after the arrival of European settlers in the 1800s. And that’s led to the return of high-intensity late dry season bushfires.

“This ecosystem-scale shock altered a carefully nurtured biodiversity established over tens of thousands of years and simultaneously increased greenhouse gas emissions,” he said.