Thunderstorms are bubbling to life across Australia this week, a trend likely to continue into December as multiple climate drivers become active and swing the odds to favour above-average rain.

On Monday alone, dozens of rain gauges across south-east Queensland and north-east NSW collected more than 50 millimetres of rain, including 108mm at Beaudesert in 24 hours, the town’s heaviest November rain on record (data exists to 1892).

The torrential falls resulted from a moist influx of air from the Coral Sea and triggered warnings for flash flooding, along with flooding along the Bremer and Logan rivers.

In drier inland regions, the threat was wind as gusts from storms on Monday afternoon reached 156 kilometres per hour at Woomera (SA) and 146kph at Julia Creek (QLD), both well above the destructive threshold of 125kph.

Humid, tropical air on Tuesday then spread further south, sparking up storms from Taroom to coastal Victoria, although the heaviest rain remained near the NSW-Queensland border.

Dangerous supercell risk today

A humid and unstable atmosphere will again fuel showers and thunderstorms on Wednesday along much of the eastern seaboard and severe thunderstorms are possible from central Queensland to central NSW.

Wednesday’s risk includes the chance of dangerous supercell thunderstorms around Brisbane, the most violent type of storm, categorised by a rotating updraft which leads to long-lived intense cells capable of producing giant hail, destructive winds, and torrential rain.

While supercells aren’t expected further south, skies over Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne are all likely to rumble with thunder on Wednesday afternoon.

After Wednesday’s explosive storms, the activity will ease slightly for a few days, however Thursday to Saturday will still serve up afternoon doses of lightning and thunder across much of the east coast and ranges, with further severe storms possible around parts of northern NSW and Queensland.

Modelling currently indicates the outbreak will then re-intensify on Sunday and extend back south to Victoria as a cold front clashes with the residing tropical air mass.

The week-long outbreak of storms follows a relatively dry start to the month and promises to deliver an average of 20 to 100mm from about Mackay to Gippsland, including around Canberra, Sydney and Brisbane.

Frequent storm events likely in the lead-up to Christmas

This week’s thundery weather pattern is likely to be repeated through the second half of November, and the Bureau of Meteorology’s latest December rain forecast also indicates a clear swing towards the month being wetter than normal.

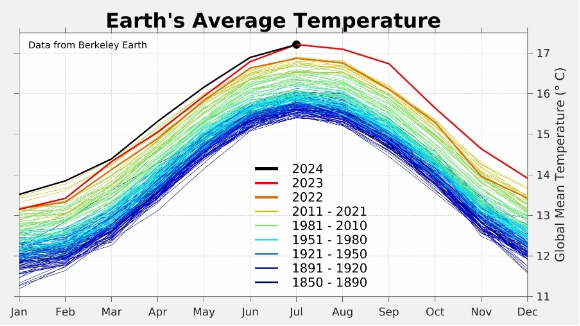

The forecast of a wet finish to 2024 is due to more than just the random variability of weather, instead being the result of numerous wet climate drivers becoming simultaneously active, all shifting into a state that favours above-average rain.

A climate driver, not to be confused with climate change, is a recurring pattern in the earth’s climate system that can alternate between opposite states, with the critical requirement that the deviations from normal occur over a sufficient region and period to impact weather patterns.

The most well-known climate drivers are the La Niña and El Niño phases of the Pacific Ocean, however a similar oscillation occurring in the Indian Ocean also impacts Australia’s weather — labelled a positive or negative Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD).

During the past 5 weeks, negative IOD values have been measured, although to be classified as an official negative IOD year these conditions need to be maintained for at least eight weeks.

On average a negative IOD occurs once every four or five years, however the recent years have already produced two events in 2021 and 2022.

A negative IOD is characterised by warmer than average seas near Indonesia and cooler seas off the Horn of Africa, a configuration which leads to a deviation of winds to a westerly across the tropical Indian Ocean.

This enhancement of westerly winds transports moisture and cloud development towards Australia — which essentially describes a similar shift in water, wind and cloud occurring during La Niña (although for the Pacific it arrives across Australia from the east).

Most negative IODs develop in either winter or early spring, meaning this year’s episode is extremely late forming whose impact will therefore be restricted to just a month or two as the arrival of the northern monsoon from December flushes out any influence from a dipole event.

While this year’s edition of a negative IOD won’t break any rain records, additional wet climate drivers have also activated during the past few weeks, raising the confidence in the wet finish to 2024 prediction:

- A positive Southern Annular Mode (SAM) has also formed across the Southern Ocean — a pattern which subdues dry westerly winds from southern Queensland to eastern Tasmania, and therefore boosts rain prospects.

- A weak La Niña like state of the Pacific Ocean may also be influencing Australia’s weather, even though the Pacific remains technically neutral.

- A pulse of tropical cloud, called an MJO, may move over Australian longitudes in early December.