Scientists say a survey of the Western Australian coast after an intense marine heatwave has revealed “heartbreaking” levels of bleaching among centuries-old coral structures.

As the scale of mortality becomes clearer, a tour operator facing booking cancellations has called for more proactive management of World Heritage-listed Ningaloo Reef.

Curtin University researchers Zoe Richards and David Juszkiewicz surveyed 21 sites along the 270-kilometre fringing reef and nearby Exmouth Gulf earlier this month.

Porites coral is showing signs of death, despite being among the most resistant to bleaching. (Supplied: David Juskiewicz)

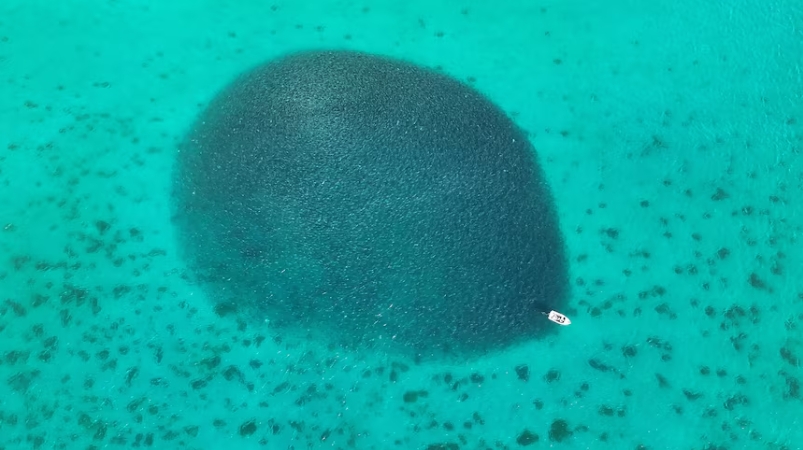

The pair say they were struck by the degree of bleaching in gigantic boulder-like bommies, or reef outcrops, comprised of a stony coral called porites.

“We went inside, swam [through the] nooks and crannies within these massive, massive corals and everything was white,” Mr Juszkiewicz said.

“This thing has been around longer than my grandparents, my great-great grandparents … it’s devastating.”

Porites bommies are popular with divers and often called the old-growth trees of the sea.

Porites are the focus of PhD candidate David Juszkiewicz’s thesis. (Supplied: Blue Media/Minderoo Foundation)

“They’re the architects of the reef … they create a lot of micro habitats for fish,” Mr Juszkiewicz said.

“These can grow as big as a townhouse and they can be hundreds of years old.

“They don’t tend to bleach so much [yet] we were coming across these large, massive porites and they were completely bleached and already showing signs of death in some locations.”

“That was probably the heartbreaking part for me.”

Researchers surveyed 21 sites along the Ningaloo Reef and nearby Exmouth Gulf. (Supplied: David Juszkiewicz)

A marine heatwave gripped half of the WA coast over summer, with warmer-than-average ocean temperatures peaking in January.

Scientists are now grasping the full extent of the damage, which included simultaneous bleaching at Ningaloo on the west coast and the Great Barrier Reef on the east.

The amount of corals that won’t recover is becoming clearer. (Supplied: Blue Media/Minderoo Foundation)

During their expedition, funded by the philanthropic Minderoo Foundation, Dr Richards and Mr Juszkiewicz found 80-to-90 per cent of corals in the northern section of the Ningaloo Reef were suffering from bleaching.

When heat stressed, corals expel a microscopic algae living in their tissues, turning them a ghostly shade of white.

Without the algae, known as zooxanthellae, the coral loses its food source, colour, and resistance to disease.

Of the area surveyed, early estimates suggest between 1 and 5 per cent of corals had already died.

For a home to more than 300 species of corals, a single percentage point represents the death of thousands of organisms.

Clarity over catastrophising

At the reef’s southern reaches, where the effects of the marine heatwave have been less severe, one of the most popular drawcards is the ancient Ayers Rock bommie.

The 8-by-6 metre landmark suffered some bleaching but locals are buoyed by signs of recovery.

Coral Bay’s most famous bommie, dubbed Ayers Rock, is believed to be hundreds of years old. (Supplied: Frazer McGregor)

Coral Bay tour operator Frazer McGregor said his business had grappled with perceptions of the reef after an unusual coral spawning killed a large number of corals and 16,000 fish in 2022.

Reports of the latest bleaching had also hurt bookings.

“People have heard in the media that the reef has been bleached and they’re like: ‘Oh, is it worth coming?'” he said.

“Rather than being Chicken Little, with the sky falling on our heads, we need to be active in managing a resource that is a public resource.”

Mr McGregor, who is also a Murdoch University coral ecologist, is confident the Ayers Rock bommie will bounce back.

“The whole thing’s not bleached, it’s just patchy,” he said.

“The anoxic event three years ago did stress it out and only about 60 to 70 per cent of it recovered and is still alive.

“So, it looks a bit motley.”

Elsewhere in Coral Bay, the impact of the marine heatwave is mixed. (Supplied: David Juszkiewicz)

As a short-term solution, Mr McGregor believes a temporary pause on recreational fishing in sanctuary zones would allow fish to go about their natural role in keeping the ecosystem healthy.

He said there should be more education for visitors, including how certain types of sunscreen could compound coral stress.

“We need to just be educating people on what we can do, so that we get the wave of support for management to be changed,” he said.

Race against rising heat

Mr Juszkiewicz echoed calls for more proactive management, with coral bleaching set to become more frequent.

Porites are critical to the structural integrity and biodiversity of the Ningaloo Reef. (Supplied: Blue Media/Minderoo Foundation)

One encouraging sign was the presence of unaffected strains throughout each surveyed site.

“Even though the majority of species were bleaching, there was that one particular colony that was hanging on full vibrant, full colour, just dealing with that heat.

“We want to sample those particular individuals that haven’t bleached and have a look at their genetic makeup and see what makes them stronger individuals.

“These are the individuals that may be used in future transplanting studies.”

Still colourful strains of coral are offering some hope for future studies. (Supplied: David Juszkiewicz)