In 1989, Zhou Xiaoping was a 29-year-old Chinese artist travelling around Australia pursuing his passion for Aboriginal culture.

He had explored the desert town of Alice Springs and the tropical Arnhem Land region before he arrived in the coastal resort of Broome. Here, immersed in an environment that felt completely foreign to him, Zhou was shocked to discover a connection to his home country.

“I met the Aboriginal songwriter Jimmy Chi,” Zhou says. “Jimmy asked me to say something to him in Chinese. He wanted to hear the sound of spoken Chinese. He then told me that his father was James Joseph Minero Chi, the son of a Chinese gold miner who had come to Australia around 1870.”

The conversation sparked Zhou’s decades-long fascination with Aboriginal-Chinese history, culture and communities, which are largely unacknowledged in either Australia or China.

Zhou was so fascinated by Aboriginal culture – and by Chi’s family history – that he relocated from Hefei, in China’s Anhui province, to Australia soon after that trip.

His years of research into Aboriginal-Chinese relations have now culminated in an exhibition he has curated at the National Museum of Australia, “Our Story: Aboriginal-Chinese People in Australia”, and a book of the same name.

In 2026, the exhibition will visit multiple venues in China, including the Guangzhou Library and the Fujian Provincial Art Museum.

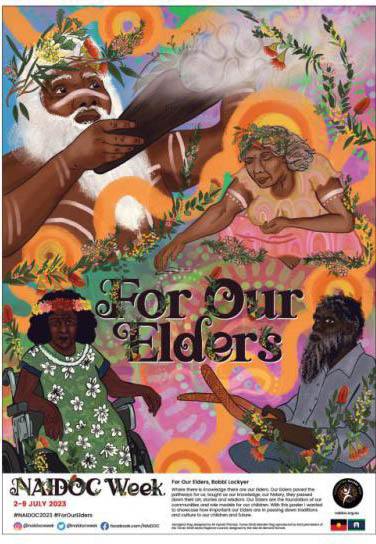

The exhibition features a mix of contemporary art, archival photographs and records, and video interviews Zhou conducted with Aboriginal-Chinese people to tell the story of relationships between the two communities in the past and the present.

The first major wave of Chinese immigration to Australia was during the gold rushes of the 1850s and 60s, when thousands of Chinese people, most of them from Guangdong and Fujian provinces, arrived in the country as indentured labourers.

By 1888, more than 7,000 Chinese people lived in Australia’s Northern Territory, vastly outnumbering the roughly 1,500 Europeans, according to government archives.

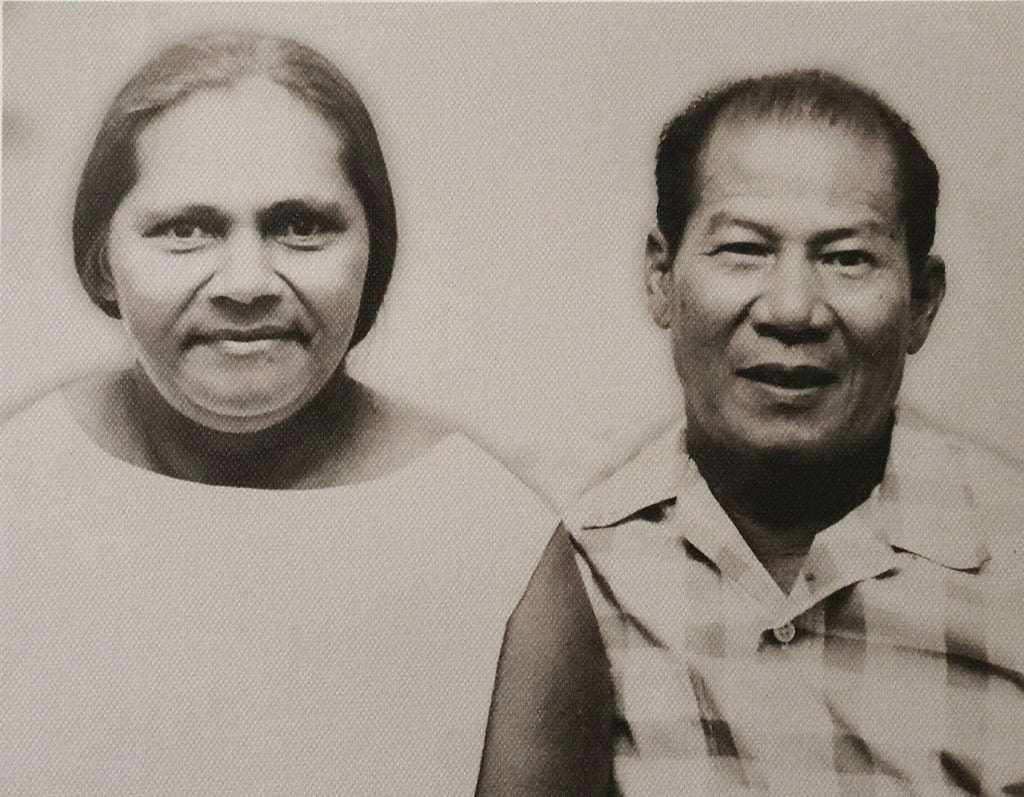

Although parts of Australia’s 19th-century economy were reliant on Chinese labourers, racist laws denied Chinese immigrants most rights and forced them to the margins of colonial society. There, many of them met Aboriginal people, who were subject to similar discrimination. Some formed relationships and families.

Racism has kept – and in some cases, still keeps – the stories of these families in the shadows. But a few artists have made their heritage a core part of their work.

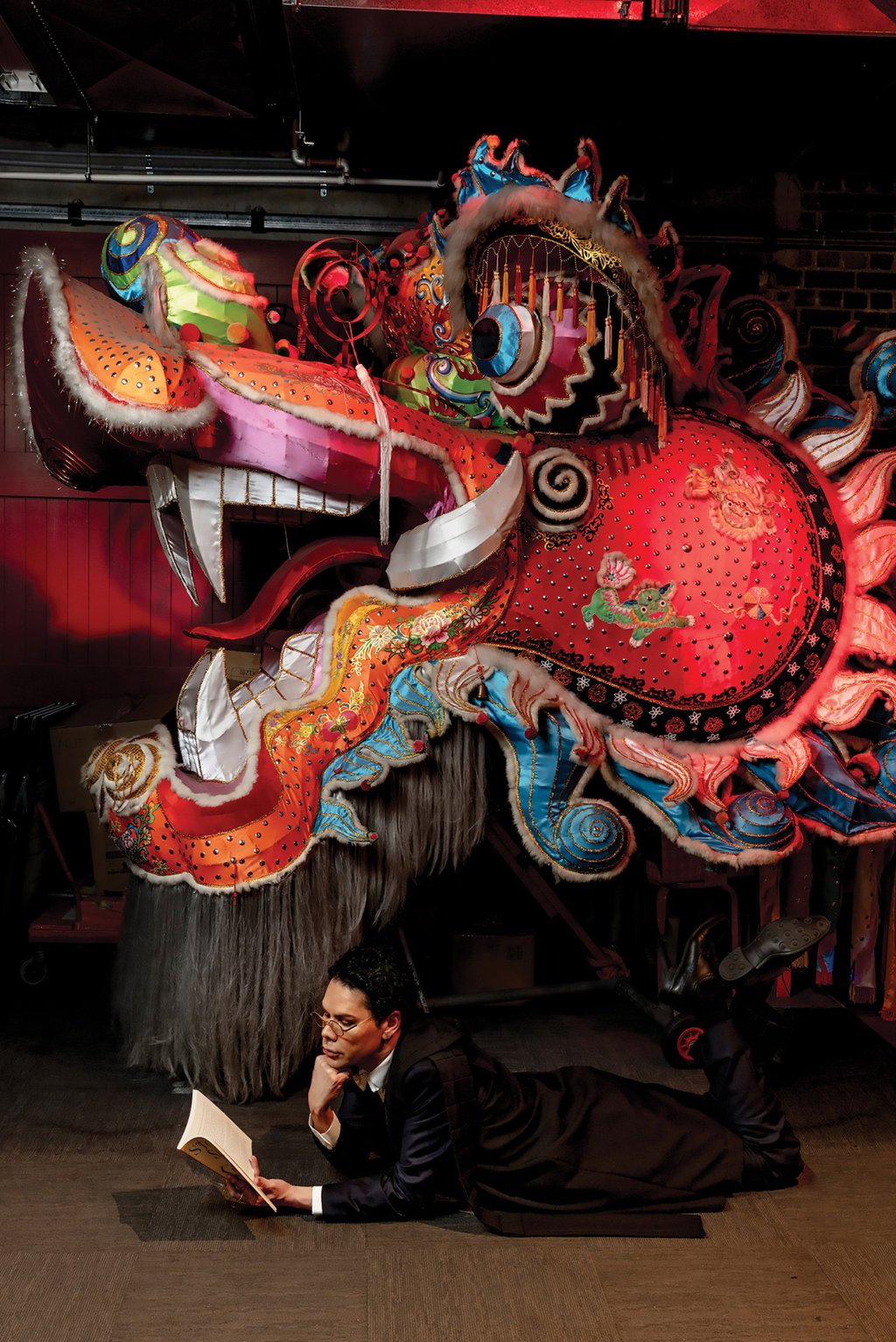

The exhibition features seven Aboriginal-Chinese artists, including Christian Thompson, who for several years has been making a series of self-portraits highlighting his Aboriginal, European and Chinese ancestry.

One photograph shows him posing with a dragon dance costume and reading the novel Stone Sky Gold Mountain by Mirandi Riwoe, a story of a Chinese family in Australia during the gold rushes, when Thompson’s ancestors arrived in Australia from southern China.

Jenna Lee has also spent years reflecting on her heritage, which includes a Chinese great-great-grandfather who moved to Australia in the late 1800s.

Lee works in multiple media, but often makes dillybags – Aboriginal string bags, normally woven from plant fibres – using unorthodox materials. “Our Story” includes Lee’s installation To Light Up: Stories, a selection of dillybags made from white and red rice and calligraphy paper that are lit from within, transforming them into Chinese lanterns.

Other artists in the exhibition have only recently begun to explore their Chinese identity.

Vernon Ah Kee, one of Australia’s most prominent Aboriginal artists, says that racism in northeast Queensland, where he grew up, meant that he felt unable to explore his Chinese heritage for decades.

He remembers feeling his community was reduced in the eyes of a racist society to “just poor Aboriginal families”, a simplification that erased their cross-cultural history.

“There was never a sense of not wanting to be Asian. There was a sense you couldn’t be,” Ah Kee said in an interview with Zhou.

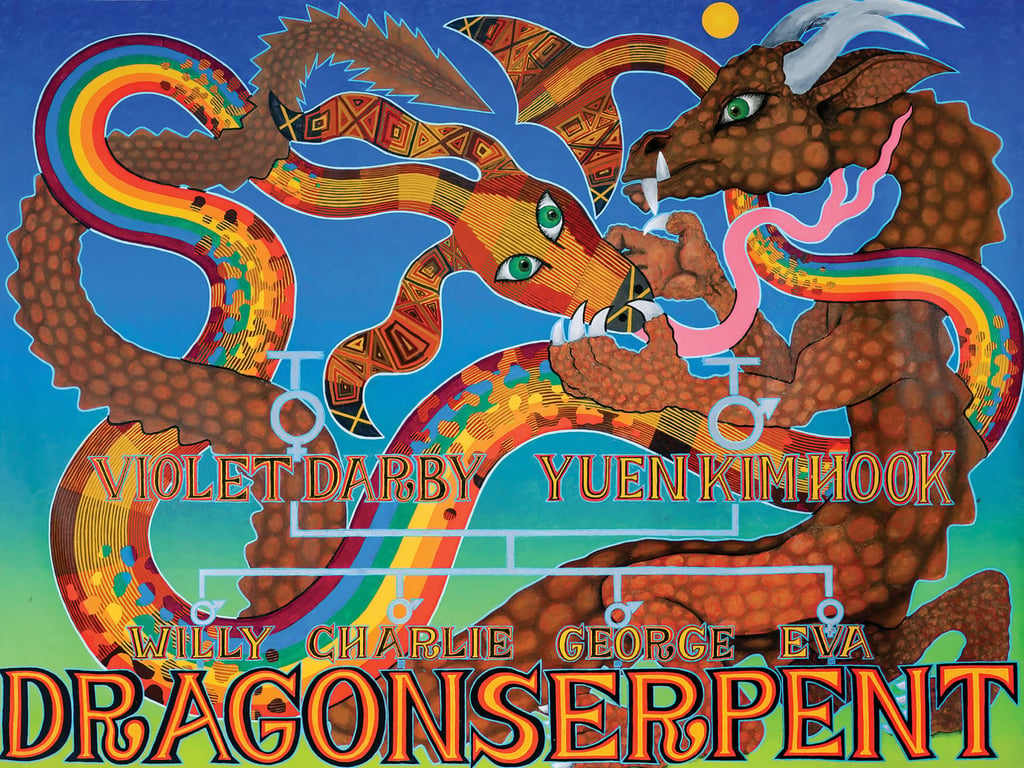

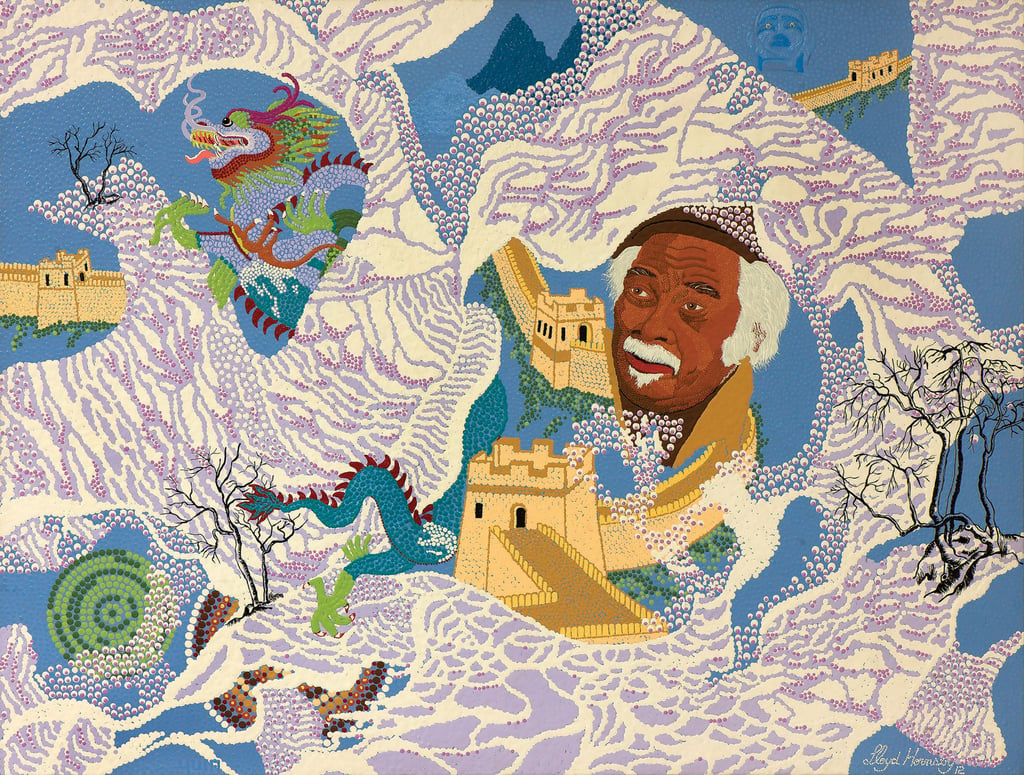

The artists are from around Australia, of different ages and work in various materials, but a few visual threads tie the disparate works together.

Several of the works include images of the Chinese dragon or the Aboriginal rainbow serpent (or both), drawing connections between the cultures’ similar mythologies.

Others reference Chinese food, alluding to the fact that, after the gold rushes, many Chinese labourers established market gardens, some of which employed Aboriginal people.

Zhou is delighted that the works tell such diverse stories of Aboriginal-Chinese life, but admits that the exhibition is just one piece of a broader initiative.

During his research, he conducted interviews with more than 100 Aboriginal-Chinese people, many of which are screened at the exhibition and recorded in the book.

They reveal that migration between China and Australia was not always one-way: some Chinese immigrants returned to China, occasionally taking their multiracial children with them.

“When the exhibition tours to China, I want to bring some of the people I’ve interviewed. They may still have relatives in China and I want to assist the families in finding their relatives,” Zhou says.

He knows it will be a challenge, but hopes that he will at least be able to help the families find records of what happened to their long-lost family members.

The project is therefore as much a social mission as it is an exhibition.

“I’ve been working with Aboriginal people for more than 30 years,” says Zhou, who has lived with Aboriginal families, learning how to live off the land and studying their art and culture.

“From the beginning, I’ve thought: what can I do to give back to them? This project is what I can do – to make people aware of this chapter of history.”

“Our Story: Aboriginal-Chinese People in Australia”, National Museum of Australia. Until January 27, 2026.