NASA’s nearly 33-year-old observatory still has plenty of top science to do, and astronomers want to extend its lifetime.

Once the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) began operations last year, the comparisons began. Astronomers and others online posted side-by-side images of the same celestial objects captured by JWST and the Hubble Space Telescope, pointing out how much crisper and more detailed those from JWST can be.JWST’s best images: spectacular stars and spiralling galaxies

But don’t count Hubble out yet. The telescope, from NASA and the European Space Agency, is still making big discoveries, after going strong for nearly 33 years.

“There’s still tons of science to be done with Hubble,” says Beth Biller, an astronomer at the University of Edinburgh, UK, who chairs a committee representing scientists who use Hubble.

“People are saying, ‘Is Hubble going to be useless now?’” adds Tom Brown, head of the Hubble mission office at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland. “It’s not, because it has unique capabilities.”

Whereas JWST detects infrared wavelengths, making it ideal for observing distant galaxies, Hubble studies the Universe mostly in other wavelengths, including high-energy ultraviolet light emitted from marvels such as exploding stars. It has sharp vision also at visible wavelengths, allowing the telescope to take unprecedented images of stars, galaxies and cosmic phenomena closer to Earth. Because no other observatory can do those jobs as broadly and as well, Hubble is still in high demand, with researchers making many more requests for its time than the telescope has available.

Astronomers want to maximize what they can get out of Hubble while it’s still useful. Engineers estimate that the US$16-billion telescope will continue working through the end of this decade and perhaps well into the 2030s. But the race is on to acquire as much science as possible in its remaining years — and to exploit its operational overlap with JWST.

The only game in town

Many astronomers are most excited about Hubble’s ability to detect UV wavelengths, which can’t be studied well from the ground — Earth’s atmosphere filters out most of that light. NASA does not plan to have another powerful UV telescope in space until the 2040s. “In the meantime, Hubble’s pretty much the only game for a huge chunk of astrophysics,” Brown says.Record number of first-time observers get Hubble telescope time

That includes UV light radiating from young stars, which glow as they gobble up gas and dust. Two years ago, STScI astronomers began surveying around 200 such stars, the largest observing programme ever done using Hubble. The goal is to create a library of UV information from these stars that future astronomers can use to understand stellar evolution. The survey is 96% complete.

Hubble also shines when studying ‘transient’ phenomena, such as exploding stars, which appear without warning in the night sky and need to be studied before they fade. Several current and planned sky surveys will spot many of these phenomena, and Hubble is uniquely suited to observing them in detail in UV or visible wavelengths as soon as they are discovered. Mission operators have even introduced ‘flexible Thursdays’ into Hubble’s schedule — one Thursday per month is devoted to scheduling last-minute observations.

Astronomers are also teaching Hubble new tricks. Operators recently worked out how to use one of its instruments, the Advanced Camera for Surveys, to combine information about the spectra and polarization of light from celestial objects, which yields new insights into their nature.

Much of the focus in the upcoming years will be to coordinate Hubble and JWST observations, to get a fuller picture of cosmic phenomena. That might mean, for instance, using Hubble to look at nearby galaxies that resemble those spotted by JWST in the distant Universe, to create a timeline of galactic evolution, or to jointly study the atmospheres of exoplanets that Hubble has a long legacy of exploring.

“The power of having both of these observatories greatly increases our ability to understand all of these areas of astrophysics,” says Jennifer Wiseman, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and Hubble’s senior project scientist. “Now is the time to be using these facilities to their fullest.”

Not dead yet

Precisely how long Hubble has left isn’t known. “If I asked you when’s your car going to break down, you’re not going to have a clue, and that’s somewhat the world we’re in,” says Jim Jeletic, Hubble’s deputy programme manager at the Goddard centre.

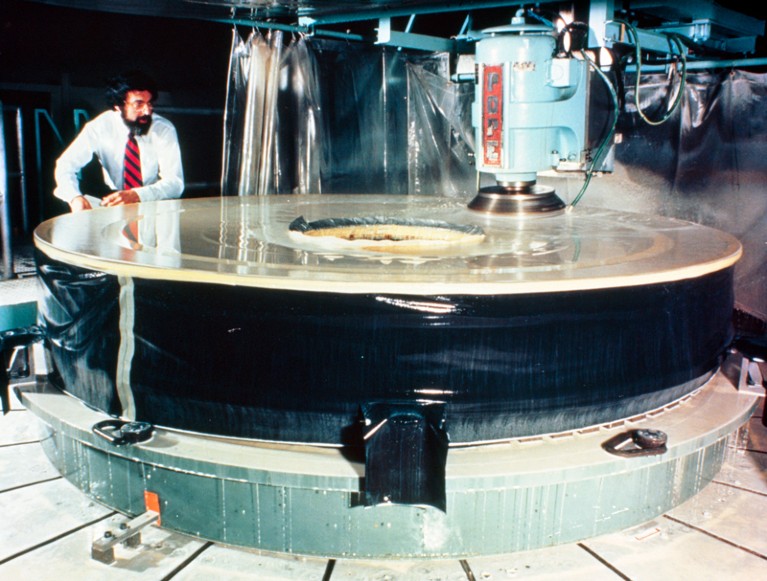

Launched in 1990 by astronauts aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery, Hubble has needed upgrades over the years. Astronauts visited it five times between 1993 and 2009, first to fix a mirror flaw that left it with blurry vision and then to enhance its scientific instruments to keep it at the cutting edge of astronomy. “That’s kept Hubble like a new observatory over and over again,” Wiseman says. But NASA retired the space shuttle in 2011, and has no plans to service the telescope again.

The basic systems that keep the telescope operating — such as the solar panels and batteries that power it, and the gyroscopes that orient it in space — are functional but ageing. Sometimes, things break with no warning, such as when Hubble’s payload computer was offline for a month in 2021. Engineers ultimately got it working again, but on a backup system. They are still trying to re-boot the initial system for Hubble to use if the backup fails.

Operators are also looking for smarter ways to run the telescope to extend its lifetime. For instance, engineers changed how Hubble communicates with satellites to relay data to Earth. Instead of using the telescope’s on-board transponders in many short bursts, mission controllers now collect more data on the telescope before sending a chunk of data all at once. Switching the transponders on and off less frequently extends their lifetime.

Getting a lift

Another long-term question is how long Hubble can stay high enough to escape the drag of Earth’s atmosphere, which brings it lower in altitude and will ultimately destroy it. In the past, the telescope has orbited as high as 615 kilometres above our planet’s surface; it is currently at 535 kilometres, where it is expected to remain until around the mid-2030s.Hubble telescope camera is broken — and US government shutdown could delay repairs

But if the Sun reaches its predicted maximum activity in 2025, solar storms could accelerate Hubble’s demise. So NASA and aerospace company SpaceX, based in Hawthorne, California, are studying whether they can attach a SpaceX capsule to Hubble and boost it to a higher orbit. That would give NASA more time to work out how to get rid of the telescope at the end of its lifetime, by guiding it down into the ocean. The results of the orbit-boosting study are not yet scheduled for public release.

“We believe we’ll be able to keep Hubble making unique and great scientific discoveries and observations into the end of this decade, if not into the next,” Jeletic says.

In the meantime, there is plenty to do. Although Hubble has taken more than 1.5 million observations in its lifetime, it has looked at less than one-tenth of one per cent of the sky.

“It’s amazing to me, this number,” Jeletic says. “There is a lot of stuff out there that we have not looked at.”