More than three-quarters of Australian students say they didn’t fully try in the latest Pisa tests, unpublished data reveals, calling into question the real source behind a continued decline in rankings.

The Programme for International Student Assessment has measured the academic performance of 15-year-olds every three years since 2000, providing the most comprehensive international rankings in science, reading and mathematics.

The latest scores, released in December, showed Australia’s year 9 students had climbed into the Top 10 of OECD countries, while continuing a longer-term trend of national decline of Australian students’ scores.

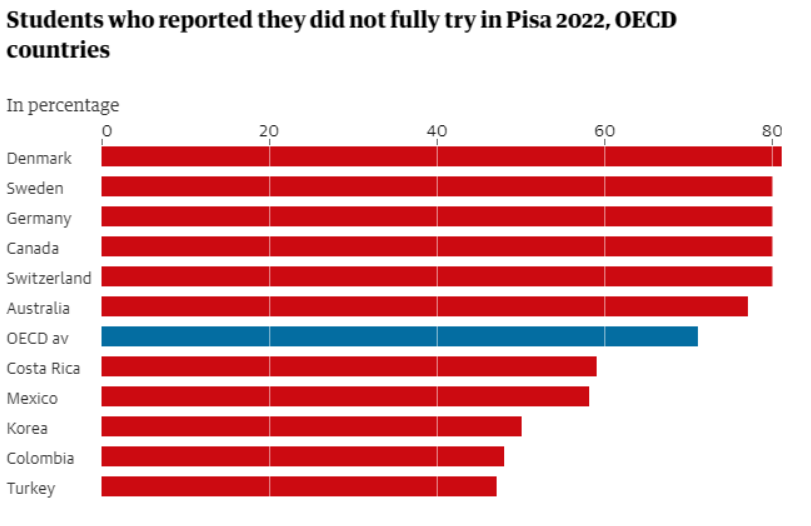

But the unpublished data, provided to the public education advocacy group Save Our Schools by the OECD, found 77% of Australian students indicated they “didn’t fully try” in the 2022 tests – the fourth equal highest of participating nations and 6% higher than the OECD average.

The national convener of Save Our Schools, Trevor Cobbold, said the results called into question the validity of the country rankings of the Pisa results.

On an effort scale of 1 to 10, Australian students reported an average score of 7.2 – indicating they would have tried harder if it had counted towards their marks.

“The high proportion of students in Australia and many other countries not fully trying indicates a broader problem, namely increasing student disaffection with learning and school,” Cobbold said.

“This appears to be a crucial factor behind declining results in many OECD countries that is often ignored in the commentary.”

Only Denmark (81%), Sweden (80%), Germany (80%), Switzerland (80%) and Belgium (78%) had a higher proportion of students who did not fully try, while Norway, the UK, Austria and high-performer Singapore had the same proportion as Australia.

In contrast, Turkey had the lowest proportion among OECD countries, with just 47% of students indicating they didn’t fully try, followed by Colombia (48%), South Korea (50%), Mexico (58%) and Costa Rica (59%).

Turkey was one of only a handful of countries whose Pisa results improved over a long-term period in the latest results.

According to the OECD, “comparisons between Pisa 2022 results and results from prior assessments may reflect differences not only in what students know and can do but how motivated they were to do their best”.

The proportion of students not fully trying has increased overall since the last time the tests were conducted in 2018. In Australia, it rose by four percentage points, compared with the OECD average of three percentage points.

Broken down by gender, female students in Australia did not fully try at a significantly higher rate to males (81% compared with 71%), a trend evident in most OECD countries.

Cobbold said country rankings could be “significantly different” based on tests where students fully try or where the proportions of students fully trying is similar across countries.

He pointed to a study by the US Bureau of Economic Research using Pisa 2015 data that employed different estimates of the proportion of students not fully trying which found significant differences in country rankings.

“The OECD’s Pisa 2022 report suggests lower student effort likely reflects lower engagement with learning and school,” Cobbold said.

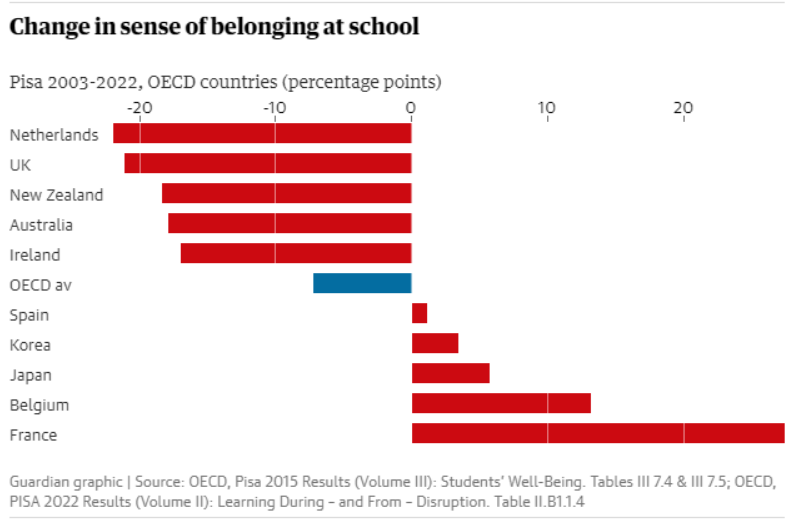

“A sense of not belonging at school can hinder learning and lead to disaffection and active disengagement from learning.”

OECD research indicates student engagement is on the decline in many OECD countries, including Australia, which has one of the highest incidences of student disaffection with school.

Approximately 30% of students reported they didn’t feel they belonged in 2022 – a fourfold increase compared with 2003 (12%) and coming at the same time of increased school refusal.

Just over one-fifth (21%) of students reported that they feel like an outsider at school, more than double 2003 (8%), with girls more likely to indicate a low sense of belonging compared with boys.

Cobbold said there appeared to be a “close relationship” with a sense of belonging and student performance in mathematics and reading scores in Pisa tests.

“While there are exceptions, most OECD countries including Australia have experienced declining student engagement with learning and school and declines in Pisa results since 2003,” he said.

“Many factors influence student achievement such as funding, teacher qualifications, teacher shortages, classroom, student absences and a range of out-of-school factors.

“It is too much to expect that schools can resolve the widespread social alienation in western countries, but they can help mitigate it with the right support.”

Pasi Sahlberg, professor in educational leadership at the University of Melbourne, said Cobbold’s findings indicated academics needed to be “more cautious” about drawing conclusions from Pisa than they currently were.

“Standardised tests don’t tell us anything about quality of teachers or teaching in schools,” he said.

“What we saw in December regarding Australia was affected by complex set of variables, including how seriously students took the test in 2022.”